![[SoundStage!]](../sslogo3.gif) The Traveler The TravelerBack Issue Article |

January 2008 Giro del Veneto: Sonus faber and Mastersound A relative latecomer to high-end audio, not having gotten into the hobby until recently, I've had a narrow agenda: wanting an audio system to capture the essence of opera, choral, and orchestral music. I'd been blown away by a performance of La Boheme at La Scala that my wife and I'd gone to on our honeymoon in Italy two years ago. Once I was back home again, I wanted a real audio system so I could enjoy this music in my everyday life. I'd not owned any high-end equipment before. Though I went frequently to live concerts, at home I'd managed with boom boxes and micro-systems for over 25 years. But, obviously, these gimcrack rigs would no longer do. In just over two years, I must've gone through a half-dozen amps, five CD players and as many sets of speakers, and moved from Rat Shack to silver to wires of copper foil. As I found my way through to equipment that played the music I liked not only competently, but gorgeously, I'd notice that, maybe six times out of ten, it was made in one small city in Italy near Venice. "It's like good wine," I thought -- terroir! "Region is all!" Reading up on it, I noticed that each factory was located in an industrial park on the outskirts of Vicenza. I'd consequently imagined Unison Research, Pathos, Sonus faber, Mastersound, Viva, and Opera all occupying the same circle drive, that they tested their stuff on the other's equipment, and that, together, they made up a kind of Disneyland of audio manufacturing. Well, those were the mythifying thoughts of a naive newcomer to hi-fi, but they aren't far from the truth. These manufacturers indeed are nearby one another (Unison Research/Opera has recently moved to Treviso, a bit to the northeast), but they do not collaborate. Each is independent and yet a deep love of music, of craftsmanship, and of life seem common to all. Recently I visited Veneto (the name for the Vicenza-Venice region) for about three days and was able to tour all but the Viva factory, which I hope to see on a return visit. I wrote ahead to all the companies more than a month before, and invitations trickled in up to the time I was about to head to Italy. My first visit was to the Sonus faber factory -- the company founded in 1980 by Franco Serblin and a group of friends exclusively to manufacture fine speakers. Now, Cesare Bevilacqua -- Serblin's partner since 1990 -- owns the company and serves as its chairman. Throughout, Sonus faber's central philosophy has contended that the speaker is a musical instrument and should have the look and feel of hand craftsmanship -- in Latin, "sonus faber" means "handmade sound." Moreover, the company has believed that the speaker should connect you to the pure emotion of the music. I myself own two different pairs of Sonus faber speakers, as I found them wonderfully suited to operatic voices and classical music. The current line includes three minimonitors, several full-range floorstanders, and speakers for home theater, all with a distinctive look inspired by Italian violin makers. Once in Vicenza, I took a 20-minute cab ride from my hotel to the outskirts of town, hopped out, opened the gate, and walked up to a gleaming glass-and-steel building. Behind an electric entrance door stenciled "Sonus faber," Giovanni Menato, Director of Marketing, was there waiting to greet me. At the Top Audio Show in Milan the week before, I'd listened to the new Auditor M (price to be announced) -- a minimonitor replacing the Cremona Auditor in the Sonus faber line. Its sound -- with Viola monoblocks, an Audio Research preamp, a Linn Sondek turntable, and Sumiko cartridge -- threw a deep and wide soundstage with fine bass warmth and created a liquid, palpable presence to the instruments and lead vocal on Tracy Chapman's eponymous first LP. It was the Auditor M I was most interested in seeing go through the manufacturing process. I'd heard that its tweeter came from the higher-end Elipsa ($20,800 per pair). After a walkthrough of the downstairs, where the first Sonus faber speaker, the Snail, is displayed, Giovanni explained that, while we would certainly see parts of the assembly and finishing, Sonus faber does not have assembly-line production of any speaker. "One day we assemble the Auditor M," he said, "Another day we assemble the baffle and mount the drivers for the Amati Anniversario."

and crossovers for the new Cremona M. He explained that the process of manufacture for any given speaker was partial -- that production was in steps and that, once a step is completed, the partial assemblies may wait a day or more before being picked up again and worked on for the next stage. On average, a minimonitor like the Auditor M takes a day to make, while a floorstander like the Amati Anniversario ($30,000 per pair) or new Cremona M ($12,000 per pair) takes two days. We'd walked past offices, through a shipping area with boxed Sonus faber speakers in white shrink-wrap and stacked on pallets ready to go, then through an inner garden of bamboo reaching toward a ceiling of skylights, and, finally, up a large staircase of shining aluminum to the main factory floor. I heard the Beatles' "Back in the U.S.S.R." playing from somewhere and saw about two dozen workers, each at a different station, bent over open speaker cabinets. The Sonus Faber factory is a sizable two stories and takes up around 2500 square meters. Twenty-two employees work in manufacturing and eight in the office -- a large staff in terms of high-end audio.

"There are many speakers all over the production floor in different stages of assembly and testing," Giovanni said, gesturing towards cabinets, crossovers, and baffles each in their own station. Giovanni took me through an area where a flotilla of drivers were waiting to be installed, to another where three men stood over a series of gleaming cabinets, stuffing handfuls of white damping fluff. There were pods of discrete activity everywhere I looked. In one corner, four or five women in aprons sat over black baffles for the Auditor M, tacking down the leather covering. In another, a man in goggles bent over gleaming metal and wires soldering crossovers, the plume of blue-gray smoke sucked away by a goosenecked duct above his hands. On a long table, cabinets of the Auditor M were being unwrapped from their protective plastic, readied for the drivers and baffle installations. And, in the middle of the floor, a tall, middle-aged man with graying hair stood over a test bench, looking at an oscilloscope, measuring the performance of an Elipsa monitor (a new home-theater speaker to be introduced at CES 2008). Giovanni said that they do not rush production, but try to guarantee each step in the chain first. "Each one works on what they are doing -- crossover, cutting and attaching the leather, testing -- until they are completely satisfied," he explained. "Then, when all is ready, each unit is tested, electronically and sonically, against the specifications of an alpha unit that is our model for how we want the speaker to perform." I came away reflecting on the serenity and good cheer of the workers. The place seemed more like a floor of draftsmen creating design drawings for a prototype rather than a factory, as, except for occasional strains of music from a testing station, it was sweetly quiet. I've been in three-star restaurants that were noisier than Sonus faber, walked into classrooms full of boisterous undergraduates where the chatter was louder. I guessed this was all part of the meticulousness, the care in manufacture, and the strong bonds of agreement regarding activity, pace, and responsibility among the workers. Their speakers are certainly elegant.

Giovanni walked me through the trophy room, a large A/V room, and then another room that was the "museum" of Sonus faber speakers of the past. Finally, he loaded me with books filled with lavish illustrations -- one of Sonus faber speakers, and another, a tribute to the history of violin-making. "Here is the book on the craftsmanship of Stradivari, Guarneri, Amati and other early violinmakers in Italy," he said. "From these we take our inspiration." Around 3:30, Giovanni drove me back across town to my hotel. I went quickly upstairs to my room, as I knew Lorenzo Sanavio of Mastersound would be by soon to take me through his factory. At 4:00 sharp, the phone rang. It was indeed Lorenzo, who was waiting for me in the lobby.

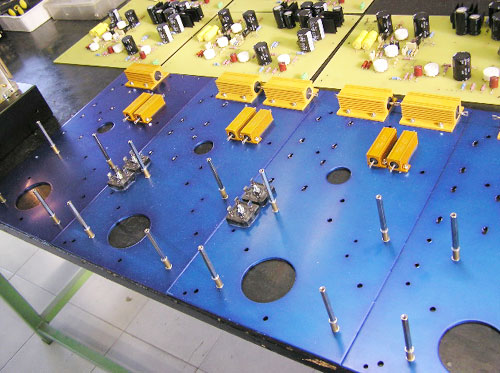

co-proprietors of Mastersound. I'd met Lorenzo at CES last year, then again at Top Audio, where I heard a system featuring Mastersound's new 845 monoblocks -- the Pf 100 Limited Edition ($39,995 per pair). With wires handmade at Mastersound, gain through the new Mastersound PH L5 preamp ($4895 with moving-magnet phono stage), and speakers designed by Lorenzo, the system sounded ultra fast and detailed with a deep and wide soundstage. It seemed to me the medium-sized hotel room was too small for the capabilities of this system, sourced by a North Star Design Sapphire CD player. It played CDs (mine) featuring the Charles Mingus quintet, Sarah Vaughan backed by musicians from the Count Basie Orchestra, and Le Concert d' Astreé performing Mozart's Mass in C Minor equally well. Here in Vicenza, Lorenzo, who is a schoolteacher by day, drove me out to his factory in a big Volvo wagon. We wended through late-afternoon traffic around a long oval ramp, then shot out on an expressway past suburbs, finally taking surface streets to the semi-industrial area where Mastersound had its factory. It is a small two-story building amidst modest residential villas, their walls ivied and gates vined with bougainvillea. We went upstairs, above the office on the first floor, to the shop on the second. From the landing, I could see that packed inside the 12-by-31-meter space were five long tables, each of which supported rows of amp chassis, test equipment, circuit boards, transformers, and boxes filled with tubes, knobs, capacitors, and resistors.

"We have here only three workers," Lorenzo said, glowing with Italian charm. "Of all Mastersound, there are five people only. With my brother -- who is engineer -- and me." He swept his arm like a maître de and invited me to enter the shop floor. Then, he pointed to each table, identifying in succession the various amps currently in production -- the Compact 300B ($5795), the Compact 845 ($5795), the EL34-powered Due Venti SE ($2995), the KT88 Due Trenta SE ($3395), and the 300B SE ($6095). I asked him what the relationship was between VAIC amps and Mastersound amps, as I'd read that the VAIC amps, one of which I owned, were designed in the old Czech Republic but assembled by Mastersound. "Is the same amp," Lorenzo said, "VAIC 300B SE is Mastersound 300B SE -- no difference in circuit or transformer. Only cosmetic -- the side and front, the name -- is different." I was delighted to hear this, of course. And I'd suspected such, as their layouts were exactly the same. Lorenzo told me that the 300B SE stereo amp was one of the last designed by his father Cesare Sanavio, who started the company in 1994, and that the newer amps in current production were done by his brother Luciano, an electrical engineer. Essentially, there are two lines of Mastersound -- the Cesare-designed line and the Luciano-designed one. Taken together, they amount to eight SET integrated amplifiers, three monoblock amplifiers, a phono stage, and the new PH L5 preamp -- a Baker's dozen of top-quality electronics in all.

It was Luciano who dreamed up the new circuitry that became the Compact 300B and Compact 845 -- zero-feedback SET integrateds. He also designed the Final 845 monoblocks ($14,995 per pair), Final 300B monoblocks ($11,695 per pair), the new preamp, and new Pf 100 Limited 845 monoblocks, which Lorenzo thought the most powerful SET amps around at 117 watts, all in class A. All Mastersound amps are zero-feedback, class-A designs, in fact. Each amp is created in stages, Lorenzo said -- a day weaving its transformers, a day assembling and soldering the boards, another day for preparing total assembly. Then, depending on the amp, complete assembly may take a half-day for the Due Venti SE or as many as two days for an 845 Reference stereo amp ($12,495). Testing involves different protocols for each amp -- some taking a half-day, others more than a day. Finally, there are three days of burn-in for each amp -- two days for the circuits and resistors without speakers and then a third day with music playing through speakers. From weaving the transformers to burn-in, the manufacture of an amp may take a full week and involve each of Mastersound's staff of five people.

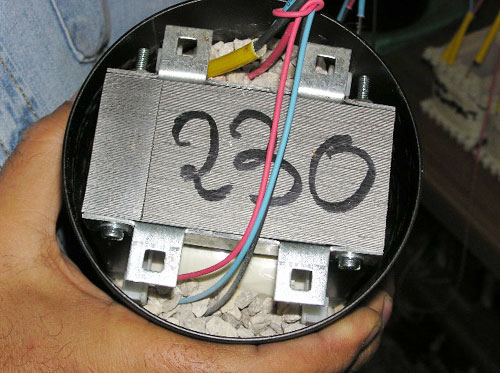

Besides the products, perhaps what was most special about Mastersound was that the company makes its own transformers right there in the shop. Lorenzo took me to a back cranny where there were two ancient winding machines sitting side-by-side on a short table. Their chassis were so worn and chipped, they looked like they'd been painted a dirty gray camouflage. Behind them was a bin full of shining copper wires of different gauges still on their spools. He picked one of them up and said, "We make transformers out of Litz wire, so soldering is not possible. You cannot cross the wires in winding, so this must be carefully done." He mentioned that the number of windings per wire was a secret, that there were numerous combinations of windings that altered the magnetics, and that the wire counts were very high. Finally, the windings are encased in a gravel-and-resin mix that makes copying the transformers impossible. If anyone attempts to cut into them to diagnose their secret, the rocks would cause so much mangling that the transformers would be destroyed without exposing their formulas. Finally, the mass and densities of the transformers is so high -- the average weight of a Mastersound amp is around 75 pounds -- they make them very difficult for any thief to steal. "You cannot carry this amp very far very fahsst," Lorenzo joked.

We finished the tour just as the sun began slanting through the doorway and windows of the shop. It was already early evening. After the factory tour, Lorenzo took me to the home of Emmanuele Perici, a friend whose large villa was the de facto and luxurious Mastersound listening room. Mr. Perici is an attorney who owns nearly a dozen Mastersound amps -- seven in one room and four others in smaller rooms throughout his spacious villa. We listened for nearly three hours to a system assembled by Lorenzo around Mastersound 845 monoblocks and custom-built Mastersound three-way speakers Lorenzo had designed just for Perici. He played audiophile discs of jazz and Italian pop, then a CD-R of a live recording from an outdoor concert former Pink Floyd bassist Roger Waters gave at the Verona amphitheater. The music flowed along with conversation, and I found myself admiring the dramatic, operatic effects of Waters' music, altogether new to me. Soundstaging and imaging were superb. We finished the evening with a patio dinner at a restaurant about a hundred yards uphill from Emmanuele Perici's door and near the lookout of Mount Berico. Lorenzo wanted us to see the misty lights of Vicenza while we dined. It was a relaxing and delicious ending to a long, intense day making new friends and discovering audio illuminations. ...Garrett Hongo |

|

![[SoundStage!]](../sslogo3.gif) All Contents All ContentsCopyright © 2008 SoundStage! All Rights Reserved |