![[SoundStage!]](../sslogo3.gif) The Vinyl Word The Vinyl WordBack Issue Article |

||||||||||||||||

August 2008 Zyx Artisan Phono Stage

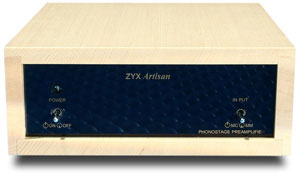

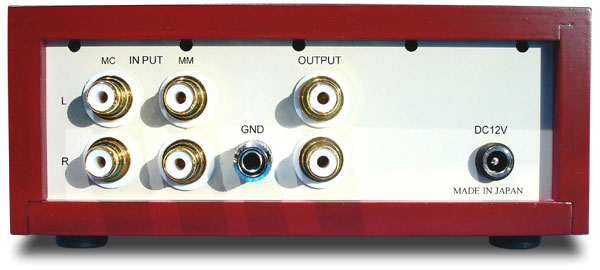

It fascinates me how Japanese culture appreciates the art of presentation and anticipation. The arrival of a silver briefcase wasn’t quite a James Bond moment, but it caused me to give care and open it slowly. Inside lay a small red box and a power coupling. Was it a Gungin thermal detonator or a Klingon cloaking device? No, it was the Artisan -- a phono stage from Hisayoshi Nakatsuka, the man behind Zyx Corporation and master maker of a line of high-end phono cartridges -- cartridges with names like Atmos and Universe. The Artisan itself looks built to hold some small but rare object d’art. Its case is made from Japanese cypress, but the use of wood is not a fashion statement. As Mr. Nakatsuka explained in correspondence: eddy currents occurring on the surface of metal containers can "disturb the sound signal." The wood is layered with five coats of semi-matt Japanese urushi -- a natural lacquer made from the hand-harvested sap of the urushi tree. The review sample came in red. Black urushi or clear urethane finishes are options. The Artisan measures a mere 6"W x 2 1/2"H x 7 1/2"D, smaller than many power supplies. If you gauge value on pounds per dollar, you will likely miss the 1 1/2-pound Artisan at its full retail of $4950 USD. Two small toggles are the only controls on the Artisan’s black faceplate: one for power, the other for switching between the moving-magnet and moving-coil RCA inputs that reside on the rear. Also backside are RCA outputs, a post for the tonearm’s ground wire, and a port for connecting a small 12V transformer that feeds DC power to the unit. That power charges nine 1.2-volt nickel-cadmium batteries that serve as capacitors for the Artisan’s low-impedance power supply. The Artisan is technically battery powered -- you can unplug it and expect it to pass the musical signal for a short time -- but it was designed to be plugged in at all times, and doing so does not change its sound for better or worse. Mr. Nakatsuka noted that the charge-discharge cycle gets shorter after a few years, but the batteries are continually charged and require no replacement. Published specs say the Artisan delivers 35dB of gain for moving-magnet cartridges and 55dB from its moving-coil outputs; however, for the latest revision of the Artisan, Mr. Nakatsuka confirmed that moving-coil gain is 60dB. Amplification occurs through four gain stages, whose even number assures the unit is in phase between input and output signals. Here, field effect transistors (FETs) do the job -- the Artisan uses no step-up transformers. From our correspondence, I understood how Nakatsuka-san pays considerable care to the physical alignment of the various bits and pieces of his circuit for maximum noise reduction, and "so as not to place magnetic materials such as a transformer and shielding metal around the circuit so that audio current flows smoothly in the parts." In fact, during the review period, the Artisan returned to Japan so Mr. Nakatsuka could change the alignment of a single part for better sound. In both materials and craftsmanship, the Artisan is a fascinating mix of the traditional and the modern. It takes a couple of weeks from start to finish to make one. Input resistors are crafted from the same super-thin, super-pure, cryogenically treated copper wire used in Zyx cartridges -- their coil geometry painstakingly hand wound to eliminate inductance. Parts get mounted on a glass-epoxy circuit board chosen for its rejection of external noise, and a special solder that generates no gas and demonstrates high durability is used. It turns out that the same solder was chosen by NASA for Space Shuttle electronics. The Artisan employs a passive CR-type RIAA equalization network built from capacitors and resistors. Mr. Nakatsuka’s idea is to avoid "a feedback circuit which disturbs a unidirectional transmission of the time-domain axis," with the goal of "[putting] back the signal to the original time domain of the sound." Indeed, that is precisely what the ideal RIAA equalizer should do, and here the Artisan’s circuit is accurate to +/- 0.2dB (20Hz-20kHz).

Mr. Nakatsuka volunteered that certain "static characteristics" (specifications) of the Artisan might be numerically inferior to those of other designs, but his approach places priority on coping with noise, with "removal of the elements harmful to sound quality." My own research suggests an equalizer based on negative feedback may provide a better signal-to-noise ratio; however, negative feedback typically varies across the frequency range and can result in reduced fidelity or a sound less rich. A CR-type equalizer may yield more stable impedance at higher frequencies. Both approaches have tradeoffs. After learning Nakatsuka-san’s design philosophy for the Artisan, I came to the conclusion that it takes one to make one. "I designed the Artisan," he wrote, "devoting purely to accurate amplification of sound." Across my conversations with designers, I’ve heard several say the same thing in different words. Wisdom to the great ones comes from listening to how their circuits serve the music, not the numbers. Review context and use In my system, Audio Physic Avanti Century speakers are connected to Atma-Sphere MA-1 Mk III mono amplifiers via Shunyata Research’s superb Orion Helix speaker cables. The amps get signal from an Atma-Sphere MP-1 Mk III full-function preamp. The MP-1 Mk III served as control center for the phono stages used for this review. It is remarkably revealing of any upstream changes. The waning days of the review period saw an Esoteric C-03 line-stage preamp join the parade. My analog front-end includes a Teres 320 turntable with SME V tonearm mounting a Transfiguration Orpheus moving-coil cartridge with 0.68mV output. The 38-pound Teres cocobolo platter is spun by a Teres Verus rim-drive system. Differently terminated but otherwise identical Silver Breeze tonearm cables from Silver Audio connect the cartridge to the RCA inputs of an Audio Research PH7 phono stage, or the XLR phono inputs of the Atma-Sphere MP-1 Mk III. Depending on the gear in use, I varied the Orpheus’s impedance load across 100-200 ohms. Interconnects and power cords come from Shunyata Research: Antares Helix (XLR and RCA) and Altair Helix (RCA) interconnects, and Andromeda, Python, and Taipan power cords -- all Helix Alpha, with one Python Helix Vx. Everything gets plugged into a Shunyata Hydra or state-of-the-art Shunyata V-Ray power conditioner. I shifted the Verus motor controller to a side table to make room for the Artisan in my rack. The wood-encased phono stage sounded best with a little space between it and other components. The diminutive red Artisan added the elegance of a boutonniere rose to a rack of tuxedo black. Its transformer cord was thin and easily routed, and I plugged it into the V-Ray. Placement of interconnects required care lest they torque the lightweight phono stage off the rack. I got to equivalent output (as checked with a dB meter) by turning down the volume of the MP-1 Mk III by two clicks when switching from the Artisan to either the MP-1 Mk III’s native phono section, which has about 60dB of gain, or the Audio Research PH7, with its 57.5dB. The Artisan had plenty of headroom for the medium-low output of the Orpheus, and gave the impression it could easily handle much lower output -- just what you’d expect of a phono stage from the manufacturer of sub-.3mV cartridges. The Artisan’s fixed 125-ohm input impedance for moving-coil cartridges worked just fine for the Transfiguration Orpheus (moving-magnet impedance is the standard 47k ohms). From my experience with a variety of adjustable phono stages, the impedance and gain parameters of the decidedly non-adjustable Artisan won’t serve every moving-coil cartridge but should hit the sweet spot for a wide range beyond those in the Zyx lineup. The Artisan's spirit Whenever a new review component arrives, I’m eager, skeptical and reluctant: eager to hear what it can do, skeptical that I’ll learn this in a few short sessions, and reluctant to wade through the typical break-in period, especially lengthy for millivolt-driven analog components like tonearm cables and phono stages. So I’m prepared to be patient while searching for true character. My take on the Artisan evolved over time, but shortly after its arrival, when I heard the opening cuckoos in Mahler’s "Titan" symphony played by the St. Louis Symphony under Leonard Slatkin [Telarc 10066], I knew right away that this phono stage came from someone with an ear for music and a keen understanding of the art of musical reproduction. My ears perked up on the very first band. There it was -- that rich rounded tonality, that vibrating column of air that came only from a wood-bodied clarinet. As a former clarinetist, I could tell Mr. Nakatsuka’s Artisan nailed this instrument right out of the box. And there was the sweet and lambent tone of a silver flute. Sections of shimmering violins betrayed a fine dynamic gradient. As I listened to the Mahler piece, my anticipation for the new quickly relaxed into enjoyment of the familiar. I like equipment that doesn’t make me think about audiophile words, and by enabling this the Artisan made a strong first impression. During my time with it, I appreciated the Artisan as one of those components whose shortcomings -- yes, it has some, and we’ll get to those -- you know are there, but you easily forgive and forget them. Despite my initial skepticism, I took to this phono stage from the start. Having used it with different phono stages, I know the Transfiguration Orpheus is a tonal-purity champ. Neither too warm nor too cool, it delivers harmonics and overtones with appealing, lifelike neutrality. This familiarity confirmed that the Artisan’s own tonal character was largely unimposing, as it yielded to the cartridge’s editorial control. If there is no component that sits perfectly in the middle of some abstract neutrality dial, then this jury found the Artisan leaning toward tonal richness and weight, but it was neither lush nor overly warm. As it proved adept in delivering tonal nuance, the Artisan never hid the gobs of sonic detail flowing through the engine of the Orpheus. It openly conveyed venue reflections and fingers sliding on cello strings. I sensed through it that circle of sonic vacuum surrounding a singer that told me he or she was in a booth, and it never lost the variety of non-musical noises (chair squeaks, page turnings) that can fall below the resolution of lesser phono stages. It was fun to follow each of the many congas, bongos, rattlers, shakers and tinkly little details all going on at once during the opening bars of "She Moves On" from Paul Simon’s Rhythm of the Saints [Warner Brothers W126098]. I heard the tremolo horn rotating in its Leslie cabinet as Willie Nelson crooned through "Moonlight in Vermont" (Stardust [Columbia JC35305]). Frankly, the Artisan was one of the most explicit phono stages I’ve heard, and its combination of tonal rightness and high resolution made for lots of late-night record-playing enjoyment. Put these attributes together and you have a component highly dexterous at unraveling musical complexity. Mendelssohn’s "Overture to Fingal’s Cave" (from Mendelssohn in Scotland [Decca/Speakers Corner SXL2246]) offered plenty of shifting dynamics as layers of string sections depicted the calm and fury of winds and waves as they lashed and lapped the rock and solitude of Scotland’s Western Highlands. There are times when Peter Maag drives the London Symphony at a healthy clip, and it’s a fun air-baton exercise. The Artisan dispatched full atmospherics, parsed instrumental sections rising in quick crescendos from forte to fortissimo, and gave no hint of running out of gas. Tiny batteries and a wall-wart transformer? The little red box delivered the dynamic goods. High frequencies from silky violins were nicely extended in Sibelius’s Fourth Symphony, from the second of von Karajan’s three Sibelius cycles [Deutsche Grammophon 2892 009], though perhaps the topmost octave from trumpets and chimes nudged a teeny bit forward. Or maybe that came from the DG engineers -- sometimes it's hard to tell. In contrast, the wood-on-metal strike of the toy xylophone on "Ice Cream Man," off Jonathan Richman’s Modern Lovers Live album [Beserkley 530055] was so fleshed out in tonal body that it startled me into one of those "instrument in the room" moments. The Artisan never evinced any harshness or glare, and detail never came off as spot-lit. But it was a wee-bit soft on leading-edge transients across all frequencies, and here my notes were consistent throughout. While it rendered the kick drum on the Nora Jones tune "In the Morning" (Feels Like Home [Blue Note 72435 84800 16]) with surprising dynamic punch and body, the Artisan also displayed a slight mid-to-low-bass ripeness. That emphasis gave weight to timpani and bass guitars, and while their strikes and plucks did not present the last word in crispness, the Artisan never veered into outright bloat. The MP-1 Mk III and Orion speaker cables are known for taut, timbral bass reproduction, so if you have a system already plummy with extended, weighty bass, the Artisan may add more. Despite gathering these minor nits over several months of careful observation, the Artisan kept whispering to me at a more limbic level to turn off the analysis and enjoy the show. On more than one occasion, while actively reviewing, I found the record had finished but my pen was no longer writing. On the backside of notes, the Artisan nicely rendered decay and reverberation to convey the ambience of the recording venue. Soloists and vocalists in front of a band had an appealing fleshed-out dimensionality. Soundstage width did not extend much beyond speaker boundaries, but with a new system layout -- the speakers in a nine-foot spread -- I hardly noticed. Soundstage depth was excellent, albeit a bit more straight-sided than obviously trapezoidal. Regardless, the Artisan’s high resolution combined with its clean separation of instrumental lines and performers to offer one of the most compelling spatial presentations of an orchestra that I’ve heard. The live recordings of Mozart works by Oleg Kagaan and Sviatoslav Richter at the Touraine Festival [EMI ASD SLS5020] offered a challenging venue for any component to reproduce. The performance was intimate, before a small audience that produced lots of ambient noise. Back-wall reflections were scant, and notes tended to trickle upward; nonetheless, a sense of air told me the musicians were in a space. Violin and piano were at different heights; the piano was miked closer to its low register and reflective off its top. Kagaan was positioned to the left front of Richter and he tended to shift about while playing. Richter’s touch on the keyboard was genius, and the tonality and dynamics captured during Kagaan’s arpeggios were sheer delight. Such was the specificity of listening with the Zyx Artisan. Spatially -- and musically -- it brought performances vividly to life. Contrast and compare I’ve been fortunate to live with two of today’s top-flight phono stages: the Audio Research PH7 ($5995) and the phono section of the Atma-Sphere MP-1 Mk III preamp ($12,100). Both have tubes in their amplification circuits and beefy power supplies, the MP-1 Mk III’s being a separate full-sized box connected by umbilical. Like the Artisan, the PH7 and MP-1 Mk III derive their gain without step-up transformers. Unlike the Artisan, both offer configurable cartridge loading and the option to use after-market power cords. Both also physically dwarf the Artisan. Would the Artisan prove a David in a room of Goliaths? It took me a while to realize what my notes did not say: The Artisan never caused me to think of it as a solid-state device. Being solid state, it had none of the rush often heard from high-gain tubed units, but neither did it exhibit a flattish dimensionality nor an overtly tight, muscular control. The Artisan did show a touch of that extended, airy tonal bloom and liquidity sometimes associated with tubes, but its sound did not cause me to think of it in terms of technology. As I said, I prefer components that don’t make me think about them apart from the music they deliver. Though it had no tube rush, the Artisan was not dead quiet; none of the units was. With my ear near the speakers, I could discern the Artisan's presence from its absence. The PH7 was the least audible of the three with no music playing. I’d just nabbed a minty copy of Elvis Costello’s My Aim is True [Columbia JC35037], from the local Half-Price Books and used it for a back-to-back between the MP-1 Mk III's phono stage and the Artisan. Tonally the Artisan had more weight and was a wee-bit warmer, but it was not quite as transparent as the Atma-Sphere preamp's phono stage, which rendered clear the raw, snarly character of Costello’s voice. His lyrics tumble out in a rush of unexpected verbal twists, and both components did an excellent job delivering them distinctly enough to follow. And both revealed that slight halo of dead air around Costello that told me he was singing from a booth. Bass guitar had a greater emphasis through the Artisan. The MP-1 Mk III did not place quite the same heaviness on bass notes, and through it they were a touch more articulated and tonally evolved. In direct comparison, the Artisan’s presentation moved the entire soundstage a couple feet forward. Neither unit held back on dynamic pop or restrained the music’s zesty forward drive, as my notebook stayed on the couch and I bopped around the room. When the music is right, I like components that make me wanna dance; my wife stood and laughed. The PH7 and MP-1 Mk III each offered slightly more golden hues from the top end of trumpets on the Slatkin Mahler piece, and higher-frequency flutes could sound a teeny bit forward with the Artisan. On the other end of the spectrum, the Artisan showed greater oomph and impact with timpani, but the MP-1 Mk III told me more about the mallet strike and kettle resonance. From all three components I heard nice air around instruments and marvelously extended decay from hard percussion, though the PH7 and MP-1 Mk III presented triangles with a crisper leading edge. All were gauged without overt warmth or analytical cool, though there were slight tonal variations across all three, and the PH7 showed a pinch more sweetness on strings and oboes that made me want more of it. For sheer unfiltered detail, such as musician noises and fingers on strings, the Artisan and MP-1 Mk III nudged out the PH7 by a half a hair. My notes reminded me that none of these differences jumped off the speakers as significant contrasts. At the end of the day, however, both the PH7 and MP-1 Mk III bore witness to their higher cost with consistently more finesse and balance across the full frequency range. But, frankly, the Artisan was a charmer, and these differences didn’t change that. I rarely comment on cost, but the reality of relative value cannot be ignored here. There are other transistor phono stages to be heard, but to date the Artisan proved itself best of that breed in my system. Conclusion It is not perfect on the leading edge or at the frequency extremes, and it is less configurable than some other units, yet the little red Zyx Artisan always seemed at home with itself. With its combination of exquisite detail retrieval, rich midrange tonality, and the ability to delineate dynamically complex musical passages, the Artisan consistently paid homage to whatever music I played through it. Across the past five years, I’ve owned or reviewed several phono stages in the Artisan’s price range and beyond, and I’ve critically listened to many others. At its list price, the Artisan offers good value, and it often sells for less. Props to Nakatsuka-san for this delightfully listenable phono stage. ...Tim Aucremann

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

![[SoundStage!]](../sslogo3.gif) All Contents All ContentsCopyright © 2008 SoundStage! All Rights Reserved |