![[SoundStage!]](../sslogo3.gif) For a Song For a SongBack-Issue Article |

|||

November 2006

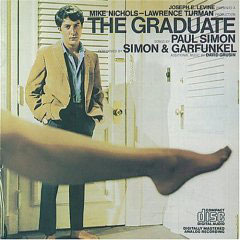

Mrs. Robinson is a character in the 1967 motion picture The Graduate. Played by Ann Bancroft, she was considered risqué, like the movie at the time of its release. She unabashedly initiates a sexual affair with the movie’s young male namesake-protagonist, played by Dustin Hoffman, a recent college graduate approximately the age of Mrs. Robinson’s daughter, whom the young man has dated, in deference to his parents, long-time friends of Mrs. & Mr. Robinson. The four parents are heavy drinkers, home bars the setting of some key scenes. More than just an individual trait or preference shared by the couples, in the late 1960s adults’ heavy alcohol use became an emblem of the hypocrisy of an "older generation" widely portrayed as self-righteously lecturing youth against drugs and imposing values contradicted by their own behavior. Welcome to your new home The voice of an alcoholism rehabilitation center director opens the song, greeting Mrs. Robinson. The staff’s wanting to know about her "for our files" shows the facility’s bureaucratic nature and its subtle dual public-relations tactic of following record-keeping rules and hinting that residents can’t fool anyone. A written record will be kept of anything they say. "We’d like to help you learn to help yourself" indicates the staff do what they do for residents’ sake, not to serve themselves -- even if one function of record-keeping might be to avoid liability or defend against accusations of mistreatment or malpractice. "Look around you. All you see are sympathetic eyes" reinforces the impression that all of this is official-speak: It is not to be trusted. An order to perceive sympathy in people rather than see for ourselves is intimidating. Staff appear sympathetic whether they are or not. Maybe contempt is what they really feel for people who can’t control their drinking, but officially they are sympathetic and supposedly helpful. Likewise, Mrs. Robinson is commanded to like the place. What is she supposed to do if she doesn’t "feel at home" soon, "stroll around the grounds" till she drops? Scene from the old home The second verse hints at the above-mentioned hypocrisy. While ostensibly teaching her daughter the right way to live, Mrs. Robinson has been hiding her drinking. The details are interesting, though. Keeping the booze with "your cupcakes" -- typically a children’s treat -- might suggest the two items belong together morally. Her not having grown up before having a child leads to excessive drinking, perhaps due to confusion, uncertainty, lack of confidence? Drinking, she avoids difficult circumstances that might help her mature further if she faced them? Part of the song’s magic is that such a small detail suggests so much. "[I]n the pantry" hints not only at where cupcakes might be stored but also at where Mrs. Robinson might store herself: in the kitchen. "[N]o one ever goes" there because neither husband nor children help mother in the kitchen. The Graduate’s audience sees Mrs. Robinson’s affair with the protagonist partly as rebellion against the socially mandated and self-enforced housewife role countless women fell into in the 1950s, when Mrs. Robinson bore her daughter. As baby-boomers grew up in the 1960s and mothers got a breather, some felt they’d let life pass them by. Some made cocktail hour a little earlier each day or swiped a little nip from the pantry at tough moments. One had to "hide it from the kids." They weren’t supposed to grow up thinking mom was a drunk or that drinking at any time of day was the way to deal with life’s difficulties. Kids also had loose lips and might tell other kids, who might spread it around. The curse of down time Mrs. Robinson’s pre-sanitarium and extra-kitchen life drives her to drink. "Sitting on a sofa on a Sunday afternoon" or "Going to the candidates’ debate" in verse 3 -- whichever she chooses, she’ll "lose." The former is too dull, the latter annoyingly inconsequential. "When you’ve got to choose" could refer to choosing between candidates as well as between sofa and debate. Neither mundane leisure activities nor political involvement fulfills Mrs. R’s needs, too deep to reach so easily. Unable to laugh away or shout away her troubles, she resorts to self-destructive behavior. Song refrains are like Greek choruses. In "Mrs. Robinson," common wisdom is tinged with facetiousness. The first two refrains toast Mrs. Robinson with a combination of mockery and sympathy -- "Here’s to you …" -- and offer salvation as salve. A better life in the hereafter has always been held out to the oppressed to prevent rebellion. But Mrs. Robinson is fairly sophisticated -- in movie and song. Reminders of Jesus’ love won’t mollify her. The final refrain rhetorically asks Joe DiMaggio where he’s gone -- where he is when he’s needed most. "A nation turns its lonely eyes to you"? DiMaggio was the quintessential secular American hero-savior: of the people, handsome, charming, widely loved and admired, superb practitioner of the national pastime, hit consecutively in 56 games in one season, even got the girl who played opposite him as female icon: Marilyn Monroe. Though still alive in Mrs. Robinson’s day, he was out of the spotlight, which now shone on counterculture heroes like this song’s writer, others linked more to political protest, even Mrs. Robinson herself as she became synonymous with a certain kind of sexual liberation. You’re still here, Mrs. Robinson? While writing this column, I heard a guest on a public-radio talk show state that she "can’t say enough bad things about the [U.S. House of Representatives] Ethics Committee" with regard to its alleged failure to take action against a representative whose name is now synonymous with sexual pursuit of Congressional pages, young persons of privilege whose prodigious resumés benefit from a flirtation with Capitol clout and who expect rewards for keeping secrets. Maybe there’s a hypocrisy gene. "Mrs. Robinson," engagingly, very succinctly, and with good-but-slightly-dark humor, sheds light on hypocrisy and the desperation people experience feeling the center coming loose. That appears to be happening today, with deception, graft, arrogance, hypocrisy, and incompetence informing an unsuccessful and costly war; the national debt soaring; environmental and other problems looming larger all the time; neither "major" political party being likely to hit such curveballs out of the park in the next few innings; and few people clamoring to surrender their material or social interests for assurances of Jesus’ love. I haven’t heard any recent singer-songwriter match the mix of artistry and substance heard in "Mrs. Robinson" and a few dozen other socially conscious songs of the '60s. Perhaps some languish unheard, with today’s commercial world unwilling to promote challenges to its own assumptions and interests but pleased to have a not-quite-ready-for-glamour-but-always-surpassingly-cool Bob Dylan hawk lingerie for Victoria’s Secret. Maybe, too, the arts are seen less today than in the '60s as wielding influence. So much official and financial wrongdoing has been perpetrated in the intervening years despite the savvy and skepticism proffered back then, who can blame us? Don’t go away -- I’ve got to check something in the pantry. ...David J. Cantor |

|||

|

|||

![[SoundStage!]](../sslogo3.gif) All Contents All ContentsCopyright © 2006 SoundStage! All Rights Reserved |