![[SoundStage!]](../sslogo3.gif) For a Song For a SongBack-Issue Article |

|||||

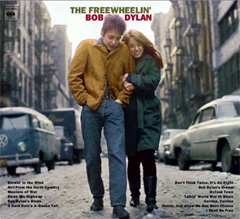

June 2005 Uneasy Listenin’: Bob Dylan’s "Blowin’ in the Wind"

"Blowin’ in the Wind" by Bob Dylan is at least somewhat familiar to millions of people beyond those who take music or songwriting seriously. "Wind" appeared on Dylan’s second LP, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, released in 1963. Peter, Paul & Mary’s pop hit rendition came out the same year. By 1964, more than 60 other professional versions of "Wind" were recorded. Even the late Pope John Paul II acknowledged the classic. At Dylan’s 1997 special appearance before him during a concert tour of Europe, the Pope said to Dylan and the audience of 300,000, "The answer to your questions about life is blowing in the wind." A religious song? A full exploration of the question, What does the phrase "blowin’ in the wind" mean? must consider a possible reference to the divine as ubiquitous and elusive yet powerful, like the wind. The questions posed in the song resemble those that people have addressed to their various gods from time immemorial. Undoubtedly the Pontiff picked up on that. However, the song never literally refers to a divine power, and "my friend," in the refrain, implies the song is sung not to a higher being but to a general audience of us mortals. If the song is not religious, it is nevertheless spiritual -- about the human spirit, morality, and the individual’s relationship to the larger world. Questions are the answer The questions that constitute the verses concern significant human shortcomings: the failure to show respect, "call him a man," despite the dignity of someone’s struggle, the "roads" he’s "walk[ed] down"; and constant warring, the need to "ban" "cannonballs" so "the white dove," foreteller of peace, can rest -- "sleep," maybe even forever "in the sand," suggesting a grave. The "mountain" in the second verse is metaphorical, as in the expression "to move mountains," referring to intractable human institutions that deny people their liberty. How do we know it isn’t just a mountain? The two questions that follow in the same verse clue us in. A mountain literally speaking has no connection to whether or not someone is "allowed to be free," whereas human institutions do. Someone who "turn[s] his head and pretend[s] that he just doesn’t see" seeks to avoid the eternal struggle for freedom, the fight against oppressive institutions. The third and final verse demands that we each take personal responsibility for redressing the injustices previously mentioned. Looking up but being unable to see the sky suggests the common experience of not perceiving something because it is as much a part of one’s milieu as the air one breathes. If we grow up in a world in which certain classes of people are denied respect, in which there is never-ending war, and in which people otherwise are unjustly killed, we assume those conditions are natural and inevitable, not subject to our will. Same old refrain: a closer look If the song exhorts people to take responsibility for ending oppression, injustice, and violence, why doesn’t it say so -- why is the answer "blowin’ in the wind" and not "get off your ass" or "kick the denial habit and get involved"? The questioning mode suggests the song is literally about questions, not answers. The fact that the only assertion is "The answer is blowin’ in the wind" supports that view. But the refrain is more specific than that alone in what it does and doesn’t say. Three questions are posed in each of the three verses, and the refrain’s assertion occurs twice -- it is conspicuous even to those not as skilled in exegesis as the Pope. His comment suggests that he also noticed the disparity between the number of questions posed and the number of answers given: nine questions, one answer. Why do all of those different questions have the same answer? It depends what "yes, ‘n’" means Perhaps surprisingly, the song’s most inconspicuous lyrics might provide a clue. Consistent with Dylan’s Freewheelin’ recording of "Wind," published versions introduce the second and third question of each verse with, "Yes, ‘n’" -- a shortened, dialectal utterance of, "Yes, and." The phrase and its specific occurrences are formal components of the song’s lyrics -- not arbitrary vocalizations of a one-time performance. The song’s questions are not individually answered, but they aren’t rhetorical questions, either -- they are not assertions in the form of questions with obvious answers. Each question not followed by the refrain is followed by "Yes" -- as if it were either a yes-or-no question or an assertion rather than a question. But it is neither of these. Then we hear "and," as if what comes next will be another assertion, though it is not. It doesn’t make sense -- according to grammar’s everyday logic. It can only be explained, then, through some other kind of logic. I think the phrase is telling the listener to hear the questions partly as assertions: such as, we all need to consider the matter of how many roads a man must walk down, how much someone must endure, before we call him a man -- before we show the person due respect or fully enfranchise the person. Saying "yes" to something means that that thing is good or acceptable. The questions posed in "Wind" are unsettling ones to listeners who are ostensibly fully socialized and hold conventional values. "Yes, ‘n’" subtly says that it’s OK to think and speak about these aspects of humanity that are usually hushed up. You won’t be ostracized -- or worse. That is consistent with "my friend" in the refrain. Otherwise, why not "The answer, I suppose, is blowin’ in the wind," which, like many other possible phrasings, could fit musically. "My friend" says the singer isn’t putting down the listener or singling out the listener as the only one who fails to prevent wars or looks up and fails to see the sky. The lyrics don’t let anyone off the hook, but they avoid pointing a finger of blame. Taken together, they insist that individually and collectively we must question our assumptions, face reality, and take responsibility for our institutions. Still in the wind Despite my analysis, the song remains enigmatic and to a degree ineffable. But it is by no means nonsensical or arbitrary -- it doesn’t merely say whatever anyone may want it to say. The lyrics’ coherence come partly from the fact that key objects or beings named in the questions are, in the actual world outside the song, literally affected by the wind: cannonballs, a white dove, a mountain, the sky. In contrast, we don’t expect something as unpredictable and uncontrollable as the wind to determine whether wars will be fought, people will be respected, we’ll be able to see the sky when we look up, or we’ll be able to hear people cry. We expect to determine those things ourselves or through our institutions. So, in one sense, yes, the answer is blowin’ in the wind, but in another sense, we’re supposed to see that the answer to moral questions is something else. We’re just not trying, we’re not paying attention, we’re concerning ourselves with trivial things when we are free to affect important matters. The answer to those questions is only "blowin’ in the wind" inasmuch as no one knows when enough people will take responsibility. Maybe that is why "Wind" is typically called a "protest song" even though it doesn’t contain any specific statement of protest. That is a significant part of the song’s genius and a source of its staying power. Consistent with the folk, blues, and rock traditions that Dylan has reinvented and expanded for more than four decades, "Blowin’ in the Wind" wears the persona of an ordinary person sharing his or her experience, not of proclamations from on high. Pronouncing the "g" of "-ing" endings is inconsistent with those traditions, though it is done successfully in some instances. The Pope’s saying "blowing" instead of "blowin’" in the comment noted at the beginning of this article suggests that he experienced the song as an outsider who perhaps gave Dylan and this song his "blessing" because he wanted in, in order to connect with the vast world of ordinary folk who were his constituents, his "flock." The song is much better known and loved than anyone’s comments about it will ever be. ...David J. Cantor |

|||||

|

|||||

![[SoundStage!]](../sslogo3.gif) All Contents All ContentsCopyright © 2005 SoundStage! All Rights Reserved |