![[SoundStage!]](../sslogo3.gif) Feature Article Feature ArticleInsiders' Forum |

|

| Many times those working within

the audio and video industries have valuable information to share with the consuming

public. However, there are few such outlets for this type of expression. The Insiders'

Forum is intended to allow industry personnel -- manufacturers, designers,

representatives, musicians, etc. -- share information with our readers on a variety of

topics. If you are an industry insider and feel that your have something valuable to

contribute, please contact the editor@soundstage.com. February 1999 A Second Marriage For Both: Surround Sound and Classical Music Try It Again by John Marks

The earlier marriage between analog surround-sound technology and classical music was an expensive and demoralizing failure. A new marriage, between classical music and the younger brother (digital surround-sound technology), has been announced. The congregation in the pews now asks themselves: Will this one last any longer, and how will those two manage to pay the rent? The marketplace failure of quadraphonic sound in the early- to mid-1970s is a business-school casebook example of how not to launch a new consumer-electronics technology. The competing home quad-sound formats (QS, SQ, and the presciently named CD-4) were technically incompatible. The esthetic benefits they delivered were questionable. Hardware and software came at substantially increased retailer inventory expense and consumer purchase cost. It added up to a quick but not at all painless death for analog quadraphonic technologies, chiefly four-channel long-playing phonograph records (Shibata stylus not included). Quad-sound software never really developed beyond the demonstration-disc stage. Pop and rock producers had the option of putting a thunderstorm in the rear channels and romantic strings in the front, or having the (mono) vocal track slowly circle the listening position. Classical-music producers were largely limited to providing ambiance on the rear channels, for which reason unusually reverberant recording venues enjoyed a brief vogue. However, there are classical compositions that have spatial effects written into their scores that intend to surround the audience with sound. Examples include antiphonal Renaissance choral and instrumental works such as those by Gabrieli; symphonic works by Berlioz, Mahler and Ives; and a number of contemporary compositions from the post-WWII period. There are certain works, such as Mahler’s Eighth Symphony, about which it can fairly be said that a stereo recording alone cannot do justice to the composer’s intentions. Quad sound’s consumer-marketplace flop was so resounding and so traumatic that the consumer electronics industry and the recorded music industry both avoided any involvement or investment in surround-sound music playback in the home for nearly 25 years. Ironically, just as the last SQ decoders and CD-4 demodulator units were slinking off to garage sales, young Hollywood film directors who were pushing the realism envelope turned to sound effects that came from behind the movie-theater audience as a means to heighten the intensity of the theatrical viewing experience. Surrounding the movie audience with loudspeakers allowed earthquakes and explosions to have greater dynamic impact, while Dolby stereo surround’s dedicated rear channels allowed for the fly-over and shoot-past spatial sound effects that helped win Apocalypse Now its Academy Award for Best Film Sound. Two years later, the thrills-and-chills bar was raised by Star Wars’ laws-of-physics-defying audible explosions in deep space. For the past 15 years, since the 1983 advent of Tomlinson Holman’s THX system-certification process, theatrical-film sound, and only theatrical-film sound, has been the impetus for surround-sound playback in the home. The truth of the matter is that surround sound for classical music is under discussion again only because home surround-sound playback technology is already installed and paid for, or soon will be. I know of nobody in the classical-music record business who claims that surround recordings of classical music would be in production now were it not for the installed base of home-theater systems. Devoted classical-music listeners are wary of the prospect of new surround music formats, while high-end audiophiles are often hostile. Living through the past two years in the classical-music recording business has been an experience that compares favorably with passage on the RMS Titanic. The commodity-ization of compact discs, combined with market saturation and a diminishing audience for classical music, has spilled barrels of red ink. Even flagship classical labels such as Deutsche Grammophon have cut back in staff and in new-release schedules.

That being the case, where do we go from here, and how do we get there? My answers are: toward more realism in classical music reproduction in the home, and by making better recordings. Something new under the sun that is both genuinely new and genuinely good is quite rare, but it does happen. I submit that one such development is AES Fellow Jerry Bruck’s (Posthorn Recordings, New York City) novel and elegant surround-sound microphone technique, Bruck KFM 360. This type of recording and playback is not two-channel stereo with ambiance channels tacked on. It is true stereophony [from the Greek words for "solid" and "sound"], which uniformly recreates the entire soundfield that surrounds an ideal listening position in the performance space. Bruck KFM 360 recordings reproduce hall ambiance more faithfully than two-channel stereo recordings are capable of doing in exactly the same way, and for exactly the same reasons, that stereo recordings reproduce the soundstage more faithfully than mono is capable of doing. Just as conventional stereo uses two microphone signals to separate and reproduce right and left soundfields, Bruck KFM 360 uses four microphone-derived signals to separate and reproduce front and rear soundfields, as well as left and right. In exactly the same way that the coherent reproduction of right and left soundfields in stereo allows for the psychoacoustic illusion of stage depth, with Bruck KFM 360 the coherent reproduction of all four soundfields allows for an unprecedented natural psychoacoustic illusion of immersion in the recording venue’s acoustic. Bruck KFM 360 utilizes two forward-facing figure-of-eight microphones on either side of a modified Schoeps KFM 6 sphere microphone. Bruck KFM 360 results in four "virtual" microphones recording a valid set of quadraphonic signals: Sphere plus 8s provide the front pair, and sphere plus polarity-inverted 8s provide the rear. This is because the sphere microphone’s electrical output has no out-of-phase component, while the figure-of-eight microphones have a non-inverting lobe at the front and a polarity-inverted lobe at the rear. As in conventional stereo M-S (mid-side) microphone technique, but turned to the side, combining the sphere and figure-of-eight microphone signals on the same side in phase cancels the rear information, leaving only front information. Combining the signal from the sphere with the figure-of-eight microphone out of phase cancels the front information, leaving only the rear information. Although it would be possible to derive front center-channel information from the Bruck KFM 360 microphone array, Bruck believes that a system of four symmetrical playback channels is sufficient for concert and acoustic music reproduction. The AES presented Bruck’s technical paper describing the Bruck KFM 360 concept at its 103rd Convention (New York, September 26-29, 1997) following a public demonstration at a meeting of AES’ New York Section. Bruck had presented an earlier paper at the biennial Tonmeistertagung in Germany, which was subsequently published in its volume of proceedings. Although Bruck has been advised that his invention is patentable, he has dedicated his invention to the public domain. Bruck hopes that the royalty-free dissemination of his microphone technique will be a spur to realistic surround-sound recordings of classical music. Bruck has designed a trademark for his technique, which he will license at no charge to any engineer or record company using it. Additionally, Schalltechnik Dr.-Ing. Schoeps GmbH of Karlsruhe, Germany, offers a ready-made Bruck KFM 360 microphone array (Model KFM 360) as an off-the-shelf item. This was introduced at the AES Convention held at San Francisco, September 26-29, 1998.

At a press reception at Hi-Fi ‘97 in San Francisco, California, I demonstrated Bruck KFM 360 playback from a Reverie master tape clone using a Nagra D four-channel digital tape deck, and four identical equidistant channels consisting of Clayton Audio amplifiers and Waveform loudspeakers. More recently, John Marks Records entered into an agreement under which laserdisc and DVD distributor Image Entertainment of Chatsworth, California will release and market the Bruck KFM 360 version of Reverie on digital audio compact discs encoded in the DTS 20-bit digital surround-sound format. Surprisingly, when the playback system is properly set up and adjusted, the difference that is noticeable when the rear channels are suddenly muted is, as the soundfield collapses to the front, the timbral balance appears to change. This demonstrates that Bruck KFM 360 does reproduce -- in the home -- the effect the hall acoustic has upon the sounds originating from the performance space’s stage. Obviously, for antiphonal works or works in which the orchestral or choral forces are intended by the composer to be distributed throughout the performance space, the difference between stereo CD playback and Bruck KFM 360 playback will be as night differs from day. My wedding toast therefore is this: "Health and happiness." ...end |

|

![[SoundStage!]](../sslogo3.gif) All Contents All ContentsCopyright © 1999 SoundStage! All Rights Reserved |

"Here’s

hoping that second marriages last longer." Foolhardy and tactless in equal

measure would be the best man who could propose such a toast, however heartfelt.

Nonetheless, most people do seem to think that second marriages go more smoothly than

first ones.

"Here’s

hoping that second marriages last longer." Foolhardy and tactless in equal

measure would be the best man who could propose such a toast, however heartfelt.

Nonetheless, most people do seem to think that second marriages go more smoothly than

first ones. The proposed second marriage

between surround sound and classical music is not so much a triumph of hope over

experience as it is an expression of the wish that people with DTS-capable home-theater

systems or DVD players will be so starved for audio-only software that they will overcome

their reluctance to buy classical music. Anyone who tells you differently probably is a

trust-fund baby.

The proposed second marriage

between surround sound and classical music is not so much a triumph of hope over

experience as it is an expression of the wish that people with DTS-capable home-theater

systems or DVD players will be so starved for audio-only software that they will overcome

their reluctance to buy classical music. Anyone who tells you differently probably is a

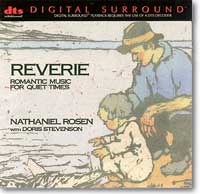

trust-fund baby.  But how does it sound? I

produced the first commercial project recorded with the Bruck KFM 360 microphone array.

That recording is International Tchaikovsky Competition Gold Medal-winning cellist

Nathaniel Rosen’s recital Reverie. The two-channel stereo release, made from

the KFM 6 Sphere channels only [John Marks Records CD JMR 10], was recognized by Stereophile

magazine as a "Record to Die For." The enhancement Bruck KFM 360 playback

provides over the ordinary stereo CD release of Reverie is subtle but worthwhile.

The perception of the enveloping hall ambiance is not confined to a "sweet

spot."

But how does it sound? I

produced the first commercial project recorded with the Bruck KFM 360 microphone array.

That recording is International Tchaikovsky Competition Gold Medal-winning cellist

Nathaniel Rosen’s recital Reverie. The two-channel stereo release, made from

the KFM 6 Sphere channels only [John Marks Records CD JMR 10], was recognized by Stereophile

magazine as a "Record to Die For." The enhancement Bruck KFM 360 playback

provides over the ordinary stereo CD release of Reverie is subtle but worthwhile.

The perception of the enveloping hall ambiance is not confined to a "sweet

spot."